Theophanu (HRR) - Wikipedia

Theophanu ( Latin and Middle Greek Θεοφανώ Theophano or Θεοφάνια Theophania ; * ca. 960, according to some sources 955, [1] in the Eastern Roman Empire ; † June 15, 991 in Nijmegen ) was the niece of the Eastern Roman Emperor John I Tzimiskes and was married as a woman Emperor Otto II 's co -empress of the Holy Roman Empire for eleven years and empress for seven years. She was one of the most influential rulers of the Middle Ages .

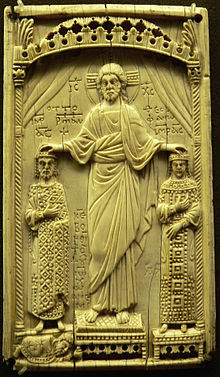

Otto II and his wife Theophanu, crowned and blessed by Christ; Ivory relief panel, circa 982/983, Milan (?), now Musée de Cluny , Paris

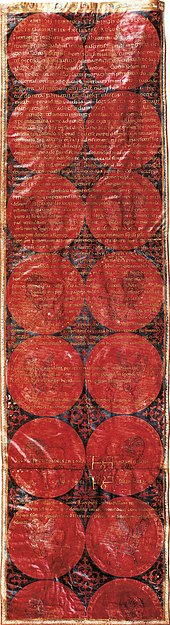

Marriage certificate of Theophanu and Otto

Statue of Theophanu in front of the market church in Eschwege

Figure of Theophanu on the town hall tower, Cologne

The name comes from Byzantine Greek : Theophaneia ( Θεοφάνεια ) means 'appearance of God' ( theophany ).

Table of Contents

Live and act

There are no sources about the origin and life of Theophanu before his marriage to Otto II. [2] Neither the place of birth nor the day of Theophanu have been handed down in writing; In particular, contrary to the customs of the time, the marriage certificate does not contain any information about the parents of the bride, who is only referred to as the niece of the Eastern Roman Emperor John I Tzimiskes (* 925; † 976; r. 969-976). She was probably the daughter of the patrikios (commander) Konstantin Skleros (* around 920; † after 989), who was a brother-in-law of Emperor Johannes Tzimiskes, since his sister Maria was his first wife. Theophanu's mother, Sophia Phokaina , was the general's daughter andKuropalates Leon Phokas , the brother of Emperor Nikephoros II. The Emperor Johannes Tzimiskes himself came from the Armenian princely house of Kurkuas (Armenian Gurgen). [3]

Otto the Great had already unsuccessfully sent two embassies to Constantinople with the aim of winning a Byzantine princess as a wife for his son. Only after a palace revolt in Byzantium, which made John I Tzimiskes emperor, did renewed negotiations take place. The third embassy, led by Archbishop Gero of Cologne , was successful, but instead of bringing Anna ( * 963 , daughter of the late Emperor Romanos II.) Theophanu to Italy, the great-niece of the deposed emperor Nikephoros and daughter-in-law of the reigning emperor Johannes Tzimiskes. There were voices recommending that the bride be sent home because the bride was not of purple descent – advice which Otto could hardly follow in view of his relations with Byzantium. [4]

Thus Theophanu was married and crowned on April 14, 972 in Rome with Otto II . [5] The marriage produced five children: Sophia , the future abbess of Gandersheim and Essen , Adelheid , the future abbess of Quedlinburg , Mathilde , the future wife of Count Palatine Ezzo , the future Emperor Otto III. and another child who apparently died early.

The marriage certificate of Theophanu shows that she was married in Rome by Pope John XIII. was crowned empress. Theophanu is frequently mentioned in the charters of Otto II (about a quarter of all charters), attesting to her privileged and influential interest in the affairs of the empire and her close association with the dignitaries of the court. [6]

Regency of Empresses (982–994)

Theophanu gave birth to four children, the three daughters Adelheid, Sophia, Mathilde and the future Emperor Otto. She accompanied her husband on a campaign against the Saracens in 982 . After the army was defeated in Capo Colonna , Otto II died unexpectedly on December 7, 983 from malaria , which was probably treated incorrectly . [6] Willigis , the archbishop of Mainz , summoned Theophanu and Adelheid , the mother of Otto II, from Italy to Germany. At the Reichstag in Rara ( Rohr near Meiningen) in 984 Henry of Bavaria surrendered, also called Henry the Brawler, as the closest male relative of the ruling dynasty, who therefore probably raised claims to the guardianship and regency and Otto III. therefore kidnapped by his mother, the already crowned and anointed king, but underage three-year-old Otto III. to Theophanu.

After a long dispute over the crown with Heinrich the Brawler, Theophanu was finally granted rulership in Frankfurt am Main in May 985, and the hereditary status of the crown in the empire was in the offing. [7] Theophanu was not related by blood to the emperors Basileios II and Constantinos VIII , who ruled in Constantinople at the same time (corresponding claims in the older literature lack any factual basis). Theophanu was regent of the East Frankish-German Empire until her death in 991, at the height of her power .

Together with her mother-in-law Adelheid, she consolidated the imperial rule, especially in Lorraine and Italy , but also on the Slavic eastern border (in 986, after several campaigns by the Empress, the Slavic princes of Bohemia and Poland appeared in peace at the Quedlinburg Court Day ). Through her clever power politics, she succeeded in persuading her son Otto III. secure the imperial throne.

Theophanu had official documents issued in the exercise of her governmental powers and thus broke through the political influence of the empresses of the Holy Roman Empire of the 10th and 11th centuries, although she was acting in the name of the imperial heir Otto III. were written. In the Ravenna charter of April 1, 990, in the Byzantine tradition, she signed as emperor (not as empress, see: Empress Eirene and Empress Theodora , who both ruled in place of their sons), impressively as Theophanius gratia divina imperator augustus("Theophanius, emperor exalted by divine grace"). Another document from the time of the stay in Italy in 990 is issued under the name of Theophanus. Only copies of both documents exist in the Vatican Library in Rome. [6] The years in the charter were counted after her, as for a male emperor, beginning with the year 972.

Empress Theophanu died after a short illness on June 15, 991 in the Palatinate Nijmegen and was buried in her widow's seat in Cologne in the abbey church of St. Pantaleon . After Theophanus' death, her mother-in-law, Empress Adelheid, was able to take over the regency for her grandson Otto III without difficulty. continue until the end of 994.

Art historical influence

Especially in the period around 1000, art in the empire was based on Byzantine models of illumination and goldsmith art ; Theophanu brought with him an entourage of artists, architects and artisans from Constantinople . the influence of the Byzantine arts spread throughout the empire. Furthermore, the spread of the Nicholas customs can be traced back to Theophanu.

Theophanu was buried at his own request in the westwork of St. Pantaleon in Cologne (her patron was Saint Pantaleon ). In 984 she had donated the relics of St. Albinus to the monastery and its church . She found her last resting place (after several reburials) in the sarcophagus made of white Naxos marble , newly designed by Sepp Hürten , in which a lead container with the few remains of the empress was embedded on December 28, 1962. [8th]

On the front side of the sarcophagus, based on the ivory relief from the 10th century shown above, a Christ crowning and blessing the ruling couple can be seen, as well as the Hagia Sophia (Constantinople) and Saint Pantaleon (Cologne), as a symbol of the united church Otto II and Theophanus times and today's desire for unity. The sarcophagus is surrounded by the following writing: Domina Theophanu, Imperatrix, uxor et mater Imperatoris, quae basilicam sancti Pantaleonis summo honore coluit et rebus propriis munificenter cumulavit, hic sepulcrum sibi constitui iussit (“The lady Theophanu, empress, wife and mother of an emperor, who showed special favor to this church of St. Panteleimon and gave it generous gifts from her property, had herself buried here”).

Every year since 1989, on June 15, the anniversary of Theophanus' death, a Eucharistic celebration has been held at the sarcophagus of the empress for the unity of Christians in East and West, whose church unity broke up in 1054. Only in 1965 were the mutual excommunications by Pope Paul VI. (Rome) and the Patriarch Athinagoras (Constantinople) abolished.

sources

- Thietmar von Merseburg, Chronicle . Retranslated and explained by Werner Trillmich . With an addendum by Steffen Patzold . (= Freiherr vom Stein commemorative edition. Vol. 9). 9th bibliographically updated edition. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2011, ISBN 978-3-534-24669-4 .

literature

- Karl Uhlirz : Theophanu . In: General German Biography (ADB). Volume 37, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1894, pp. 717-722.

- Adelbert Davids (ed.): The Empress Theophanu. Byzantium and the West at the turn of the first millennium. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1995 ISBN 0-521-52467-9 .

- Ekkehard Eickhoff : Theophanu and the King. Otto III and his world. Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-608-91798-5 .

- Odilo Engels , Peter Schreiner (ed.): The encounter of the West with the East. Congress proceedings of the 4th symposium of the Mediävistenverband in Cologne in 1991 on the occasion of the 1000th anniversary of the death of Empress Theophanu. Sigmaringen 1993.

- Heike Hawicks: Theophanu. In: Amalie Fößel (ed.): The Empresses of the Middle Ages. Pustet, Regensburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-7917-2360-0 , pp. 60-77.

- Heike Hawicks: Theophanu. In: Eva Labovie (ed.): Women in Saxony-Anhalt. A biographical-bibliographical lexicon from the Middle Ages to the 18th century. Böhlau, Cologne/Weimar/Vienna 2016, ISBN 978-3-412-50128-0 , pp. 358–364.

- Anton von Euw, Peter Schreiner (ed.): Empress Theophanu. Meeting of East and West at the turn of the first millennium. Commemorative writing on the 1000th anniversary of the Empress's death. Schnütgen Museum, Cologne 1991 (2 vols.) ISBN 978-2-263-02698-0 .

- Anton von Euw , Peter Schreiner (ed.): Art in the Age of Empress Theophanu. Punch, 1993, ISBN 978-3-9801801-4-6 .

- Hans K. Schulze , The Marriage Certificate of Empress Theophanu, Hanover 2007 ISBN 978-3-7752-6124-1

- Gunther Wolf (ed.): Empress Theophanu. Princess from abroad - the great empress of the western empire. Böhlau, Cologne 1991, ISBN 3-412-05491-7 .

- Peter von Steinitz (ed.): Theophanu Governing Empress of the Western Empire, Pantaleon writings, Verlag Freundeskreis St. Panthaleon, 5th edition, Cologne, ISBN 3-9805197-1-6

Remarks

- ↑ Cf. Gunther Wolf: Again to the question: Who was Theophano? In: id., Empress Theophanu. Princess from abroad - the western empire's great empress , Cologne 1991, p. 67. Hans K. Schulze, The Marriage Certificate of Empress Theophanu. The Greek Empress and the Holy Roman Empire 972–991 , Hanover 2007, p. 42.

- ↑ Heike Hawicks: Theophanu. In: Amalie Fößel (ed.): The Empresses of the Middle Ages. Regensburg 2011, pp. 60–77, here p. 60.

- ↑ See HK Ter Sahakean. The Armenian emperor of Byzantium , Venice 1905 (in Armenian). See the review by A. Merk SJ, in: Byzantine Journal , Volume 19, Leipzig 1910, pp. 547-550; Franz Tinnefeld : Byzantine foreign marriage policy from the 9th to the 12th century. Continuity and change of principles and practical aims. In: Byzantinoslavica. Revue Internationale des Etudes Byzantines. Prague 1993, pp. 21–28. Walter Deeters: On the Marriage Certificate of the Empress Theophanu . In: Brunswick yearbook. 54, 1973, pp. 9–23 ( online ).

- ^ Cf. Helmut Fussbroich: Theophanu. The Greek woman on the German imperial throne. Cologne 1991, p. 41.

- ↑ Heike Hawicks: Theophanu. In: Amalie Fößel (ed.): The Empresses of the Middle Ages. Regensburg 2011, pp. 60–77, here p. 62.

- ↑ a b c Moses Sotiriadis: Theophanu the Princess of Eastern Rome . 5th edition. Circle of Friends of St. Pantaleon eV, Cologne, ISBN 3-9805197-1-6 , pp. 10–15 .

- ↑ Heike Hawicks: Theophanu. In: Amalie Fößel (ed.): The Empresses of the Middle Ages. Regensburg 2011, pp. 60–77, here p. 68.

- ↑ Karl-Josef Baum: Short guide through the Romanesque parish church of St. Pantaleon in Cologne . Publisher: Circle of Friends of St. Pantaleon Cologne eV 2nd edition. Cologne 2001, pp. 1–2 .

predecessorgovernment officesuccessor

Adelheid of BurgundyRoman-German Queen

from 985 to 991Adelheid of Burgundy (guardianship)

Cunégonde of Luxembourg