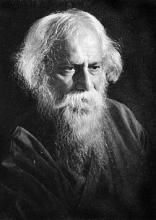

BEING THE HIBBERT LECTURES FOR 1930 THE RELIGION OF MAN

RABINDRANATH TAGORJS THE HIBBERT LECTURES FOR 1922

NEW YORK THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1931

COPYRIGHT, 1931, BY THE MACM1LLAN COMPANY.

All rights reserved no part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. Set up and elcctrotypcd Published February, 193

8T W BY MAWtf WKmiRltS WKOTVWtfl MIHTBri IK TI1K UNITXD MATft tif A V1RU'A

TO DOROTHY ELMHIRST

PREFACE

THE chapters included in this book, which comprises the Hibbert Lectures delivered in Oxford, at Manchester College, during the month of May 1930, contain also the gleanings of my thoughts on the same subject from the harvest of many lectures and addresses delivered in different countries of the world over a considerable period of my life.

The fact that one theme runs through all only proves to me that the Religion of Man has been growing within my mind as a religious experience and not merely as a philosophical subject In fact, a very large portion of my writings, beginning from the earlier products of my immature youth down to the present time, carry an almost continuous trace of the history of this growth. Today I am made conscious of the fact that the works that I have started and the words that I have uttered are deeply linked by a unity of inspiration whose proper definition has often remained unrevealed to me.

In the present volume I offer the evidence of my own personal life brought into a definite focus. To some of my readers this will supply matter of psychological interest; but for others I hope it will carry with It its own ideal value important for such a subject as religion. (p-7) My sincere thanks are due to the Hibbert Trustees, and especially to Dr. W. H. Drummond, with whom I have been in constant correspondence, for allowing me to postpone the delivery of these Hibbert Lectures from the year 1928, when I was too ill to proceed to Europe, until the summer of 1930. I have also to thank the Trustees for their very kind permission given to me to present the substance of the lectures in this book in an enlarged form by dividing the whole subject into chapters instead of keeping strictly to the lecture form in which they were delivered in Oxford* May I add that the great kindness of my hostess, Mrs. Drummond, in Oxford, will always remain in my memory along with these lectures as intimately associated with them?

In the Appendix I have gathered together from my own writings certain parallel passages which bring the reader to the heart of my main theme. Furthermore, two extracts, which contain historical material of great value, are from the pen of my esteemed colleague and friend, Professor KshitI Mohan Sen, To him I would express my gratitude for the help he has given me in bringing before me the religious ideas of medieval India which* touch the subject of my lectures.

RABINDMNATH TAGORE September 1930

CONTENTS

I. MAN'S UNIVERSE

II. THE CREATIVE SPIRIT

III. THE SURPLUS IN MAN

IV. SPIRITUAL UNION

V. THE PROPHET

VI. THE VISION

VII. THE MAN OF MY HEART

VIII. THE MUSIC MAKER

IX. THE ARTIST

X. MAN'S NATURE

XI. THE MEETING

XII. THE TEACHER

XIII. SPIRITUAL FREEDOM

XIV. THE FOUR STAGES OF LIFE

XV. CONCLUSION

APPENDIX

I. THE BAÜL SINGERS OF BENGAL

II. A CONVERSATION BETWEEN EINSTEIN AND TAGORE

III. DADU AND THE MYSTERY OF FORM

IV. AN ADDRESS IN MANCHESTER COLLEGE OXFORD

The eternal Dream

. is borne on the wings of ageless Light that rends the veil of the vague

. and goes across Time weaving ceaseless patterns of Being.

. The mystery remains dumb,

. the meaning of this pilgrimage,

. the endless adventure of existence whose rush along the sky

. flames up into innumerable rings of paths, till at last knowledge gleams out from the dusk in the infinity of human spirit,

. and in that dim lighted dawn

. she speechlessly gazes through the break in the mist at the vision of Life and of Love

. rising from the tumult of profound pain and joy,

Santiniketan

. September 16, 1939

. (Composed for the Opening Day Celebrations of the Indian College, Montpelier, France.)

Chapter I

MAN'S UNIVERSE

LIGHT, as the radiant energy of creation, started the ringdance of atoms in a diminutive sky, and also the dance of the stars in the vast, lonely theatre of time and space* The planets came out of their bath of fire and basked in the sun for ages. They were the thrones of the gigantic Inert, dumb and desolate, which knew not the meaning of its own blind destiny and majestically frowned upon a future when its monarchy would be menaced.

Then came a time when life was brought into the arena in the tiniest little monocycle of a cell. With its gift of growth and power of adaptation it faced the ponderous enormity of things, and contradicted the unmeaningness of their bulk. It was made conscious not of the volume but of the value of existence, which it ever tried to enhance and maintain in manybranched paths of creation, overcoming the obstructive inertia of Nature by obeying Nature's law*

But the miracle of creation did not stop here in this isolated speck of life launched on a lonely voyage to the Unknown. A multitude of cells were bound together into a larger unit, not through aggregation, but through a marvellous quality of complex interrelationship maintaining a perfect coordination of functions. This is the creative principle of unity, the divine mystery of existence, that baffles all analysis. The larger cooperative units could adequately pay for a greater freedom of selfexpression, and they began to form and develop in their bodies new organs of power, ne\v instruments of efficiency. This was the march of evolution ever unfolding the potentialities of life,

But this evolution which continues on the physical plane has its limited range. All exaggeration in that direction becomes a burden that breaks the natural rhythm of life, and those creatures that encouraged their ambitious flesh to grow in dimensions have nearly all perished of their cumbrous absurdity.

Before the chapter ended Man appeared and turned the course of this evolution from an indefinite march of physical aggrandisement to a freedom of a more subtle perfection. This has made possible his progress to become unlimited, and has enabled him to realize the boundless in his power,

The fire is lighted, the hammers are working, and for laborious days and nights amidst dirt and discordance the musical instrument is being made, We may accept this as a detached fact and follow its evolution* But when the music is revealed, we know that the whole thing is a part of the manifestation of music in spite of its contradictory character. The process of evolution, which after ages has reached man, must be realized in its unity with him; though in him it assumes a new value and proceeds to a different path. It is a continuous process that finds its meaning in Man ; and we must acknowledge that the evolution which Science talks of is that of Man's universe. The leather binding and titlepage are parts of the book itself ; and this world that we perceive through our senses and mind and life's experience is profoundly one with ourselves.

The divine principle of unity has ever been that of an inner interrelationship. This is revealed in some of its earliest stages in the evolution of multicellular life on this planet. The most perfect inward expression has been attained by man in his own body. But what is most important of all is the is the fact that man has also attained its realization in a more subtle body outside his physical system. He misses himself when isolated; he finds his own larger and truer self in his wide human relationship, His multicellular body is born and it dies; his multipersonal humanity is immortal In this ideal of unity he realizes the eternal in his life and the boundless in his love. The unity becomes not a mere subjective idea, but an energizing truth. Whatever name may be given to it, and whatever form it symbolizes, the consciousness of this unity is spiritual, and our effort to be true to it is our religion. It ever waits to be revealed in our history in a more and more perfect illumination.

We have our eyes, which relate to us the vision of the physical universe. We have also an inner faculty of our own which helps us to find our relationship with the supreme self of man, the universe of personality. This faculty is our luminous imagination, which in its higher stage is special to man. It offers us that vision of wholeness which for the biological necessity of physical survival is superfluous; its purpose is to arouse in us the sense of perfection which is our true sense of immortality. For perfection dwells ideally in Man the Eternal, inspiring love for this ideal in the individual, urging him more and more to realize it.

The development of intelligence and physical power is equally necessary in animals and men for their purposes of living; but what is unique in man is the development of his consciousness which gradually deepens and widens the realization of his immortal being, the perfect, the eternal. It inspires those creations of his that reveal the divinity in him which is his humanity in the varied manifestations of truth, goodness and beauty, in the freedom of activity which is not for his use but for his ultimate expression* The individual man must exist for Man the great, and must express him in disinterested works, in science and philosophy, (p-14) in literature and arts, in service and worship. This is his religion, which is working in the heart of all his religions in various names and forms. He knows and uses this world where it is endless and thus attains greatness, but he realizes his own truth where it is perfect and thus finds his fulfilment,

The idea of the humanity of our God, or the divinity of Man the Eternal, is the main subject of this book. This thought of God has not grown in my mind through any process of philosophical reasoning* On the contrary, it has followed the current of my temperament from early days until it suddenly flashed into my consciousness with a direct vision. The experience which I have described in one of the chapters which follow convinced me that on the surface of our being we have the everchanging phases of the individual self, but in the depth there dwells the Eternal Spirit of human unity beyond our direct knowledge. It very often contradicts the trivialities of our daily life, and upsets the arrangements made for securing our personal exclusiveness behind the walls of individual habits and superficial conventions. It inspires in us works that are the expressions of a Universal Spirit; it invokes unexpectedly in the midst of a selfcentred life a supreme sacrifice. At its call, we hasten to dedicate our lives to the cause (p-15) of truth and beauty, to unrewarded service of others, in spite of our lack of faith in the positive reality of the ideal values.

During the discussion of my own religious experience I have expressed my belief that the first stage of my realization was through my feeling of intimacy with Nature not that Nature which has its channel of information for our mind and physical relationship with our living body, but that which satisfies our personality with manifestations that make our life rich and stimulate our imagination in their harmony of forms, colours, sounds and movements. It is not that world which vanishes into abstract symbols behind its own testimony to Science, but that which lavishly displays its wealth of reality to our personal self having its own perpetual reaction upon our human nature.

I have mentioned in connection with my personal experience some songs which I had often heard from wandering village singers, belonging to a popular sect of Bengal, called Baüls (* Se Appendix I), who have no images, temples, scriptures, or ceremonials, who declare in their songs the divinity of Man, and express for him an intense feeling of love. Coming from men who are unsophisticated, living a simple life in obscurity, it gives us a clue to the inner meaning of all religions. For it sug* gests that these religions are never about a God of (p-16) cosmic force, but rather about the God of human personality.

At the same time it must be admitted that even the impersonal aspect of truth dealt with by Science belongs to the human Universe. But men of Science tell us that truth, unlike beauty and goodness, is independent of our consciousness. They explain to us how the belief that truth is independent of the human mind is a mystical belief, natural to man but at the same time inexplicable. But may not the explanation be this, that ideal truth does not depend upon the individual mind of man, but on the universal mind which comprehends the individual? For to say that truth, as we see it, exists apart from humanity is really to contradict Science itself; because Science can only organize into rational concepts those facts which man can know and understand, and logic is a machinery of thinking created by the mechanic man.

The table that I am using with all its varied meanings appears as a table for man through his special organ of senses and his special organ of thoughts* When scientifically analysed the same table offers an enormously different appearance to him from that given by his senses. The evidence of his physical senses and that of his logic and his scientific instruments are both related to his own power of comprehension; both are true and true for him. He makes use of the table with full confidence for his physical purposes, and with equal confidence makes intellectual use of it for his scientific knowledge. But the knowledge is his who is a man. If a particular man as an individual did not exist, the table would exist all the same, but still as a thing that is related to the human mind. The contradiction that there is between the table of our sense perception and the table of our scientific knowledge has its compon centre of reconciliation in human personality.

The same thing holds true in the realm of idea. In the scientific idea of the world there is no gap in the universal law of causality. Whatever happens could never have happened otherwise. This is a generalization which has been made possible by a quality of logic which is possessed by the human mind. But this very mind of Man has its immediate consciousness of will within him which is aware of its freedom and ever struggles for it. Every day in most of our behaviour we acknowledge its truth; in fact, our conduct finds its best value in its relation to its truth. Thus this has its analogy in our daily behaviour with regard to a table. For whatever may be the conclusion that Science has unquestionably proved about the table, we are amply rewarded when we deal with it as a solid fact and never as a crowd of fluid elements that represent a certain kind of energy. We can (p-18) also utilize this phenomenon of the measurement The space represented by a needle when magnified by the microscope may cause us no anxiety as to the number of angels who could be accommodated on its point or camels which could walk through its eye. In a cinemapicture our vision of time and space can be expanded or condensed merely according to the different technique of the instrument. A seed carries packed in a minute receptacle a future which is enormous in its contents both in time and space. The truth, which is Man, has not emerged out of nothing at a certain point of time, even though seemingly it might have been manifested then. But the manifestation of Man has no end in itself not even now. Neither did it have its beginning in- any particular time we ascribe to it The truth of Man is in the heart of eternity, the fact of it being evolved through endless ages. If Man's manifestation has round it a background of millions of lightyears, still it is his own background. He includes in himself the time, however long, that carries the process of his becoming, and he is related for the very truth of his existence to all things that surround him.

Relationship is the fundamental truth of this world of appearance. Take, for instance, a piece of coal When we pursue the fact of it to its ultimate composition, substance which seemingly is the most stable element in it vanishes in centres of revolving forces. These are the units, called the elements of carbon, which can further be analysed into a certain number of protons and electrons. Yet these electrical facts are what they are, not in their detachment, but in their interrelationship, and though possibly some day they themselves may be further analysed, nevertheless the pervasive truth of interrelation which is manifested in them will remain.

We do not know how these elements, as carbon, compose a piece of coal ; all that we can say is that they build up that appearance through a unity of interrelationship, which unites them not merely in an individual piece of coal, but in a comradeship of creative coordination with the entire physical universe.

Creation has been made possible through the continual selfsurrender of the unit to the universe. And the spiritual universe of Man is also ever claiming selfrenunciation from the individual units. This spiritual process is not so easy as the physical one in the physical world, for the intelligence and will of the units have to be tempered to those of the universal spirit

It is said in a verse of the Upanishad that this world which is all movement is pervaded by one supreme unity, and therefore true enjoyment can never be had through the satisfaction of greed, but (p-20) only through the surrender of our individual self to the Universal Self.

There are thinkers who advocate the doctrine of the plurality of worlds, which can only mean that there are worlds that are absolutely unrelated to each other. Even if this were true it could never be proved. For our universe is the sum total of what Man feels, knows, imagines, reasons to be, and of whatever is knowable to him now or in another time. It affects him differently in its different aspects, in its beauty, its inevitable sequence of happenings, its potentiality; and the world proves itself to him only in its varied effects upon his senses, imagination and reasoning mind.

I do not imply that the final nature of the world depends upon the comprehension of the individual person* Its reality is associated with the universal human rnind which comprehends all time and all possibilities of realization. And this is why for the accurate knowledge of things we depend upon Science that represents the rational mind of the universal Man, and not upon that of the individual who dwells in a limited range of space and time and the immediate needs of life. And this is why there is such a thing as progress in our civilization; for progress means that there is an ideal perfection which the individual seeks to reach by extending his limits in knowledge, power, love, enjoyment, thus approaching the universal. The (p-21) most distant star, whose faint message touches the threshold of the most powerful telescopic vision, has its sympathy with the understanding mind of man, and therefore we can never cease to believe that we shall probe further and further into the mystery of their nature. As we know the truth of the stars we know the great comprehensive mind of man.

We must realize not only the reasoning mind, but also the creative imagination, the love and wisdom that belong to the Supreme Person, whose Spirit is over us all, love for whom comprehends love for all creatures and exceeds in depth and strength all other loves, leading to difficult endeavours and martyrdoms that have no other gain than the fulfilment of this love itself.

The Isha of our Upanishad, the Super Soul, which permeates all moving things, is the God of this human universe whose mind we share in all our true knowledge, love and service, and whom to reveal in ourselves through renunciation of self is the highest end of life.

Chapter II

THE CREATIVE SPIRIT

ONCE, during the improvisation of a story by a young child, I was coaxed to take my part as the hero. The child imagined that I had been shut in a dark room locked from the outside. She asked me, "What will you do for your freedom?" and I answered, "Shout for help". But, however desirable that might be if it succeeded immediately, it would be unfortunate for the story. And thus she in her imagination had to clear the neighbourhood of all kinds of help that my cries might reach. I was compelled to think of some violent means of kicking through this passive resistance ; but for the sake of the story the door had to be made of steel. I found a key, but it would not fit, and the child was delighted at the development of the story jumping over obstructions.

Life's story of evolution, the main subject of which is the opening of the doors of the dark dungeon, seems to develop in the same manner. Difficulties were created, and at each offer of an answer the story had to discover further obstacles in order to carry on the adventure. For to come to an absolutely satisfactory conclusion is to come to the end of all things, and in that case the great child would (p-33) have nothing else to do but to shut her curtain and go to sleep.

The Spirit of Life began her chapter by introducing a simple living cell against the tremendously powerful challenge of the vast Inert. The triumph was thrillingly great which still refuses to yield its secret She did not stop there, but defiantly courted difficulties, and in the technique of her art exploited an element which still baffles our logic.

This is the harmony of selfadjusting interrelationship impossible to analyse. She brought close together numerous cell units and, by grouping them into a selfsustaining sphere of cooperation, elaborated a larger unit It was not a mere agglomeration. The grouping had its caste system in the division of functions and yet an intimate unity of kinship. The creative life summoned a larger army of cells under her command and imparted into them, let us say, a communal spirit that fought with all its might whenever its integrity was menaced.

This was the tree which has its inner harmony and inner movement of life in its beauty, its strength, its sublime dignity of endurance, its pilgrimage to the Unknown through the tiniest gates of reincarnation. It was a sufficiently marvellous achievement to be a fit termination to the creative venture. But the creative genius cannot stop (p-24) exhausted ; more windows have to be opened ; and she went out of her accustomed way and brought another factor into her work, that of locomotion. Risks of living were enhanced, offering opportunities to the daring resourcefulness of the Spirit of Life. For she seems to revel in occasions for a fight against the giant Matter, which has rigidly prohibitory immigration laws against all newcomers from Life's shore. So the fish was furnished with appliances for moving in an element which offered its density for an obstacle. The air offered an even more difficult obstacle in its lightness; but the challenge was accepted, and the bird was gifted with a marvellous pair of wings that negotiated with the subtle laws of the air and found in it a better ally than the reliable soil of the stable earth. The Arctic snow set up its frigid sentinel; the tropical desert uttered in its scorching breath a gigantic "No" against all life's children. But those peremptory prohibitions were defied, and the frontiers, though guarded by a death penalty, were triumphantly crossed.

This process of conquest could be described as progress for the kingdom of life. It journeyed on through one success to another by dealing with the laws of Nature through the help of the invention of new instruments. This field of life's onward march is a field of ruthless competition. Because the material world is the world of quantity, where (p-25) resources are limited and victory waits for those who have superior facility in their weapons, therefore success in the path of progress for one group most often runs parallel to defeat in another.

It appears that such scramble and fight for opportunities of living among numerous small combatants suggested at last an imperialism of big bulky flesh a huge system of muscles and bones, thick and heavy coats of armour and enormous tails. The idea of such indecorous massiveness must have seemed natural to life's providence; for the victory in the world of quantity might reasonably appear to depend upon the bigness of dimension. But such gigantic paraphernalia of defence and attack resulted in an utter defeat, the records of which every day are being dug up from the desert sands and ancient mud flats. These represent the fragments that strew the forgotten paths of a great retreat in the battle of existence. For the heavy weight which these creatures carried was mainly composed of bones, hides, shells, teeth and claws that were nonliving, and therefore imposed its whole huge pressure upon life that needed freedom and growth for the perfect expression of its own vital nature. The resources for living which the earth offered for her children were recklessly spent by these megalomaniac monsters of an immoderate appetite for the sake of maintaining a cumbersome system of dead burdens that thwarted (p-26) them in their true progress. Such a losing game has now become obsolete. To the few stragglers of that party, like the rhinoceros or the hippopotamus, has been allotted a very small space on this earth, absurdly inadequate to their formidable strength and magnitude of proportions, making them look forlornly pathetic in the sublimity of their incongruousness. These and their extinct forerunners have been the biggest failures in life's experiments. And then, on some obscure dusk of dawn, the experiment entered upon a completely new phase of a disarmament proposal, when little Man made his appearance in the arena, bringing with him expectations and suggestions that are unfathomably great.

We must know that the evolution process of the world has made its progress towards the revelation of its truth that is to say some inner value which is not in the extension in space and duration in time. When life came out it did not bring with it any new materials into existence. Its elements are the same which are the materials for the rocks and minerals. Only it evolved a value in them which cannot be measured and analysed. The same thing is true with regard to mind and the consciousness of self ; they are revelations of a great meaning, the selfexpression of a truth. In man this truth has made its positive appearance, and is struggling to make its manifestation more and more clear. That (p-27) which is eternal is realizing itself in history through the obstructions of limits.

The physiological process in the progress of Life's evolution seems to have reached its finality in man. We cannot think of any noticeable addition or modification in our vital instruments which we are likely to allow to persist. If any individual is born, by chance, with an extra pair of eyes or ears, or some unexpected limbs like stowaways without passports, we are sure to do our best to eliminate them from our bodily organization. Any new chance of a too obviously physical variation is certain to meet with a determined disapproval from man, the most powerful veto being expected from his aesthetic nature, which peremptorily refuses to calculate advantage when its majesty is offended by any sudden license of form. We all know that the back of our body has a wide surface practically unguarded. From the strategic point of view this oversight is unfortunate, causing us annoyances and indignities, if nothing worse, through unwelcome intrusions. And this could reasonably justify in our minds regret for retrenchment in the matter of an original tail, whose memorial we are still made to carry in secret But the least attempt at the rectification of the policy of economy in this direction is indignantly resented. I strongly believe that the idea of ghosts had its best chance with our timid imagination in (p-28) our sensitive back a field of dark ignorance; and yet it is too late for me to hint that one of our eyes could profitably have been spared for our burdencarrier back, so unjustly neglected and haunted by undefined fears.

Thus, while all innovation is stubbornly opposed, there is every sign of a comparative carelessness about the physiological efficiency of the human body. Some of our organs are losing their original vigour. The civilized life, within walled enclosures, has naturally caused in man a weakening of his power of sight and hearing along with subtle sense of the distant. Because of our habit of taking cooked food we give less employment to our teeth and a great deal more to the dentist. Spoilt and pampered by clothes, our skin shows lethargy in its function of adjustment to the atmospheric temperature and in its power of quick recovery from hurts.

The adventurous Life appears to have paused at a crossing in her road before Man came. It seems as if she became aware of wastefulness in carrying on her experiments and adding to her inventions purely on the physical plane. It was proved in Life's case that four is not always twice as much as two. In living things it is necessary to keep to the limit of the perfect unit within which the interrelationship must not be inordinately strained* The ambition that seeks power in the (p-29) augmentation of dimension is doomed; for that perfection which is in the inner quality of harmony becomes choked when quantity overwhelms it in a fury of extravagance. The combination of an exaggerated nose and arm that an elephant carries hanging down its front has its advantage. This may induce us to imagine that it would double the advantage for the animal if its tail also could grow into an additional trunk. But the progress which greedily allows Life's field to be crowded with an excessive production of instruments becomes a progress towards death. For Life has its own natural rhythm which a multiplication table has not; and proud progress that rides roughshod over Life's cadence kills it at the end with encumbrances that are unrhythmic. As I have already mentioned, such disasters did happen in the history of evolution.

The moral of that tragic chapter is that if the tail does not have the decency to know where to stop, the drag of this dependency becomes fatal to the body's empire.

Moreover, evolutionary progress on the physical plane inevitably tends to train up its subjects into specialists. The camel is a specialist of the desert and is awkward in the swamp. The hippopotamus which specializes in the mudlands of the Nile is helpless in the neighbouring desert Such onesided emphasis breeds professionalism in Life's (p-30) domain, confining special efficiencies in narrow compartments. The expert training in the aerial sphere is left to the bird ; that in the marine is particularly monopolized by the fish. The ostrich is an expert in its own region and would look utterly foolish in an eagle's neighbourhood. They have to remain permanently content with advantages that desperately cling to their limits. Such mutilation of the complete ideal of life for the sake of some exclusive privilege of power is inevitable; for that form of progress deals with materials that are physical and therefore necessarily limited.

To rescue her own career from such a multiplying burden of the dead and such constriction of specialization seems to have been the object of the Spirit of Life at one particular stage. For it does not take long to find out that an indefinite pursuit of quantity creates for Life, which is essentially qualitative, complexities that lead to a vicious circle. These primeval animals that produced an enormous volume of flesh had to build a gigantic system of bones to carry the burden. This required in its turn a long and substantial array of tails to give it balance. Thus their bodies, being compelled to occupy a vast area, exposed a very large surface which had to be protected by a strong, heavy and capacious armour. A progress which represented a congress of dead materials required a parallel organization of teeth and claws, or horns and hooves, which also were dead.

In its own manner one mechanical burden links itself to other burdens of machines, and Life grows to be a carrier of the dead, a mere platform for machinery, until it is crushed to death by its interminable paradoxes. We are told that the greater part of a tree is dead matter; the big stem, except for a thin covering, is lifeless. The tree uses it as a prop in its ambition for a high position and the lifeless timber is the slave that carries on its back the magnitude of the tree. But such a dependence upon a dead dependant has been achieved by the tree at the cost of its real freedom. It had to seek the stable alliance of the earth for the sharing of its burden, which it did by the help of secret underground entanglements making itself permanently stationary.

But the form of life that seeks the great privilege of movement must minimize its load of the dead and must realize that life's progress should be a perfect progress of the inner life itself and not of materials and machinery; the nonliving must not continue outgrowing the living, the armour deadening the skin, the armament laming the arms.

At last, when the Spirit of Life found her form in Man, the effort she had begun completed its cycle, and the truth of her mission glimmered into suggestions which dimly pointed to some direction (p-32) of meaning across her own frontier. Before the end of this cycle was reached, all the suggestions had been external. They were concerned with technique, with life's apparatus, with the efficiency of the organs. This might have exaggerated itself into an endless boredom of physical progress. It can be conceded that the eyes of the bee possessing numerous facets may have some uncommon advantage which we cannot even imagine, or the glowworm that carries an arrangement for producing light in its person may baffle our capacity and comprehension. Very likely there are creatures having certain organs that give them sensibilities which we cannot have the power to guess.

All such enhanced sensory powers merely add to the mileage in life's journey on the same road lengthening an indefinite distance. They never take us over the border of physical existence.

The same thing may be said not only about life's efficiency, but also life's ornaments. The colouring and decorative patterns on the bodies of some of the deep sea creatures make us silent with amazement The butterfly's wings, the beetle's back, the peacock's plumes, the shells of the crustaceans, the exuberant outbreak of decoration in plant life, have reached a standard of perfection that seems to be final. And yet if it continues in the same physical direction, then, however much variety of surprising excellence it may produce, it leaves out (p-33) some great element of unuttered meaning. These ornaments are like ornaments lavished upon a captive girl, luxuriously complete within a narrow limit, speaking of a homesickness for a far away horizon of emancipation, for an inner depth that is beyond the ken of the senses. The freedom in the physical realm is like the circumscribed freedom in a cage. It produces a proficiency which is mechanical and a beauty which is of the surface. To whatever degree of improvement bodily strength and skill may be developed they keep life tied to a persistence of habit It is closed, like a mould, useful though it may be for the sake of safety and precisely standardized productions. For centuries the bee repeats its hive, the weaverbird its nest, the spider its web; and instincts strongly attach themselves to some invariable tendencies of muscles and nerves never being allowed the privilege of making blunders. The physical functions, in order to be strictly reliable, behave like some model schoolboy, obedient, regular, properly repeating lessons by rote without mischief or mistake in his conduct, but also without spirit and initiative. It is the flawless perfection of rigid limits, a cousin possibly a distant cousin of the inanimate.

Instead of allowing a full paradise of perfection to continue its tame and timid rule of faultless regularity the Spirit of Life boldly declared for (p-34) a further freedom and decided to eat of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. This time her struggle was not against the Inert, but against the limitation of her own overburdened agents. She fought against the tutelage of her prudent old prime minister, the faithful instinct She adopted a novel method of experiment, promulgated new laws, and tried her hand at moulding Man through a history which was immensely different from that which went before. She took a bold step in throwing open her gates to a dangerously explosive factor which she had cautiously introduced into her council the element of Mind. I should not say that it was ever absent, but only that at a certain stage some curtain was removed and its play was made evident, even like the dark heat which in its glowing intensity reveals itself in a contradiction of radiancy.

Essentially qualitative, like life itself, the Mind does not occupy space. For that very reason it has jio bounds in its mastery of space. Also, like Life, Mind has its meaning in freedom, which it missed in its earliest dealings with Life's children. In the animal, though the mind is allowed to come out of the immediate limits of livelihood, its range is restricted, like the freedom of a child that might run out of its room but not out of the house; or, rather, like the foreign ships to which only a certain port was opened in Japan in the beginning of (p-35) her contact with the West in fear of the danger that might befall if the strangers had their uncontrolled opportunity of communication. Mind also is a foreign element for Life; its laws are different, its weapons powerful, its moods and manners most alien.

Like Eve of the Semitic mythology, the Spirit of Life risked the happiness of her placid seclusion to win her freedom. She listened to the whisper of a tempter who promised her the right to a new region of mystery, and was urged into a permanent alliance with the stranger. Up to this point the interest of life was the sole interest in her own kingdom, but another most powerfully parallel interest was created with the advent of this adventurer Mind from an unknown shore. Their interests clash, and complications of a serious nature arise. I have already referred to some vital organs of Man that are suffering from neglect. The only reason has been the diversion created by the Mind interrupting the sole attention which Life's functions claimed in the halcyon days of her undisputed monarchy. It is no secret that Mind has the habit of asserting its own will for its expression against life's will to live and enforcing sacrifices from her. When lately some adventurers accepted the dangerous enterprise to climb Mount Everest, it was solely through the instigation of the archrebel Mind. In this case Mind denied its treaty of cooperation with its partner and ignored Life's claim to help in her living. The immemorial privileges of the ancient sovereignty of Life are too often flouted by the irreverent Mind; in fact, -all through the course of this alliance there are constant cases of interference with each other's functions, often with unpleasant and even fatal results. But in spite of this, or very often because of this antagonism, the new current of Man's evolution is bringing a wealth to his harbour infinitely beyond the dream of the creatures of monstrous flesh.

The manner in which Man appeared in Life's kingdom was in itself a protest and a challenge, the challenge of Jack to the Giant. He carried in his body the declaration of mistrust against the crowding of burdensome implements of physical progress. His Mind spoke to the naked man, "Fear not"; and he stood alone facing the menace of a heavy brigade of formidable muscles. His own puny muscles cried out in despair, and he had to invent for himself in a novel manner and in a new spirit of evolution. This at once gave him his promotion from the passive destiny of the animal to the aristocracy of Man* He began to create his further body, his outer organs the workers which served him and yet did not directly claim a share of his life. Some of the earliest in his list were bows and arrows. Had this change been undertaken by the physical process of evolution, modifying his arms in a slow and gradual manner, it might have resulted in burdensome and ungainly apparatus. Possibly, however, I am unfair, and the dexterity and grace which Life's technical instinct possesses might have changed his arm into a shooting medium in a perfect manner and with a beautiful form. In that case our lyrical literature today would have sung in praise of its fascination, not only for a consummate skill in hunting victims, but also for a similar mischief in a metaphorical sense. But even in the service of lyrics it would show some limitation. For instance, the arms that would specialize in shooting would be awkward in wielding a pen or stringing a lute. But the great advantage in the latest method of human evolution lies in the fact that Man's additional new limbs, like bows and arrows, have become detached. They never tie his arms to any exclusive advantage of efficiency.

The elephant's trunk, the tiger's paws, the claws of the mole, have combined their best expressions in' the human arms, which are much weaker in their original capacity than those limbs I have mentioned. It would have been a hugely cumbersome practical joke if the combination of animal limbs had had a simultaneous location In the human organism through some overzeal in biological inventiveness. (p-38)

The first great economy resulting from the new programme was the relief of the physical burden, which means the maximum efficiency with the minimum pressure of taxation upon the vital resources of the body. Another mission of benefit was this, that it absolved the Spirit of Life in Man's case from the necessity of specialization for the sake of limited success. This has encouraged Man to dream of the possibility of combining in his single person the fish, the bird and the fleetfooted animal that walks on land. Man desired in his completeness to be the one great representative of multiform life, not through wearisome subjection to the haphazard gropings of natural selection, but by the purposeful selection of opportunities with the help of his reasoning mind. It enables the schoolboy who is given a penknife on his birthday to have the advantage over the tiger in the fact that it does not take him- a million years to obtain its possession, nor another million years for its removal, when the instrument proves unnecessary or dangerous. The human mind has compressed ages into a few years for the acquisition of steelmade claws. The only cause of anxiety is that the instrument and the temperament which uses it may not keep pace in perfect harmony. In the tiger, the claws and the temperament which only a tiger should possess have had a synchronous development, and in no single tiger is any maladjustment possible between its nails and its tigerliness. But the human boy, who grows a claw in the form of a penknife, may not at the same time develop the proper temperament necessary for its use which only a man ought to have. The new organs that today are being added as a supplement to Man's original vital stock are too quick and too numerous for his inner nature to develop its own simultaneous concordance with them, and thus we see everywhere innumerable schoolboys in human society playing pranks with their own and other people's lives and welfare by means of newly acquired penknives which have not had time to become humanized.

One thing, I am sure, must have been noticed that the original plot of the drama is changed, and the mother Spirit of Life has retired into the background, giving full prominence, in the third act, to the Spirit of Man though the dowager queen, from her inner apartment, still renders necessary help. It is the consciousness in Man of his own creative personality which has ushered in this new regime in Life's kingdom. And from now onwards Man's attempts are directed fully to capture the government and make his own Code of Legislation prevail without a break. We have seen in India those who are called mystics, impatient of the continued regency of mother Nature in their own (p-40) body, winning for their will by a concentration of inner forces the vital regions with which our masterful minds have no direct path of communication.

But the most important fact that has come into prominence along with the change of direction in our evolution, is the possession of a Spirit which has its enormous capital with a surplus far in excess of the requirements of the biological animal in Man. Some overflowing influence led us over the strict boundaries of living, and offered to us an open space where Man's thoughts and dreams could have their holidays. Holidays are for gods who have their joy in creation. In Life's primitive paradise, where the mission was merely to live, any luck which came to the creatures entered in from outside by the donations of chance; they lived on perpetual charity, by turns petted and kicked on the back by physical Providence. Beggars never can have harmony among themselves; they are envious of one another, mutually suspicious, like dogs living upon their master's favour, showing their teeth, growling, barking, trying to tear one another. This is what Science describes as the struggle for existence. This beggars' paradise lacked peace ; I am sure the suitors for special favour from fate lived in constant preparedness, inventing and multiplying armaments. (p-41)

But above the din of the clamour and scramble rises the voice of the Angel of Surplus, of leisure, of detachment from the compelling claim of physical need, saying to men, "Rejoice". From his original serfdom as a creature Man takes his right seat as a creator. Whereas, before, his incessant appeal has been to get, now at last the call comes to him to give. His God, whose help he was in the habit of asking, now stands Himself at his door and asks for his offerings. As an animal, he is still dependent upon Nature; as a Man, he is a sovereign who builds his world and rules it

And there, at this point, comes his religion, whereby he realizes himself in the perspective of the infinite. There is a remarkable verse in the Atharva Veda which says: "Righteousness, truth, great endeavours, empire, religion, enterprise, heroism and prosperity, the past and the future, dwell in the surpassing strength of the surplus."

What is purely physical has its limits like the shell of an egg ; the liberation is there in the atmosphere of the infinite, which is indefinable, invisible. Religion can have no meaning in the enclosure of mere physical or material interest; it is in the surplus we carry around our personality the surplus which is like the atmosphere of the earth, bringing to her a constant circulation of light and life and delightfulness* (p-42) I have said in a poem of mine that when the child is detached from its mother's womb it finds its mother in a real relationship whose truth is in freedom. Man in his detachment has realized himself in a wider and deeper relationship with the universe. In his moral life he has the sense of his obligation and his freedom at the same time, and this is goodness. In his spiritual life his sense of the union and the will which is free has its culmination in love. The freedom of opportunity he wins for himself in Nature's region by uniting his power with Nature's forces. The freedom of social relationship he attains through owning responsibility to his community, thus gaining its collective power for his own welfare. In the freedom of consciousness he realizes the sense of his unity with his larger being, finding fulfilment in the dedicated life of an everprogressive truth and everactive love.

The first detachment achieved by Man is physical. It represents his freedom from the aecessity of developing the power of his senses and limbs in the limited area of his own physiology, having for itself an unbounded background with an immense result in consequence. Nature's original intention was that Man should have the allowance of his sightpower ample enough for his surroundings and a little over. But to have to develop an astronomical telescope on our skull would cause (p-43) a worse crisis of bankruptcy than it did to the Mammoth whose densely foolish body indulged in an extravagance of tusks. A snail carries its house on its back and therefore the material, the shape and the weight have to be strictly limited to the capacity of the body. But fortunately Man's house need not grow on the foundation of his bones and occupy his flesh. Owing to this detachment, his ambition knows no check to its daring in the dimension and strength of his dwellings. Since his shelter does not depend upon his body, it survives him. This fact greatly affects the man who builds a house, generating in his mind a sense of the eternal in his creative work. And this background of the boundless surplus of time encourages architecture, which seeks a universal value overcoming the miserliness of the present need.

I have already mentioned a stage which Life reached when the units of single cells formed themselves into larger units, each consisting of a multitude. It was not merely an aggregation, but had a mysterious unity of interrelationship, complex in character, with differences within of forms and function. We can never know concretely what this relation means, There are gaps between the units, but they do not stop the binding force that permeates the whole. There is a future for the whole which is in its growth, but in order to bring this (p-44) about each unit works and dies to make room for the next worker. While the unit has the right to claim the glory of the whole, yet individually it cannot share the entire wealth that occupies a history yet to be completed.

Of all creatures Man has reached that multicellular character in a perfect manner, not only in his body but in his personality. For centuries his evolution has been the evolution of a consciousness that tries to be liberated from the bonds of individual separateness and to comprehend in its relationship a wholeness which may be named Man. This relationship, which has been dimly instinctive, is ever struggling to be fully aware of itself. Physical evolution sought for efficiency in a perfect communication with the physical world; the evolution of Man's consciousness sought for truth in a perfect harmony with the world of personality.

There are those who will say that the idea of humanity is an abstraction, subjective in character. It must be confessed that the concrete objectiveness of this living truth cannot be proved to its own units. They can never see its entireness from outside; for they are one with it The individual cells of our body have their separate lives; but they never have the opportunity of observing the body as a whole with its past, present and future. If these cells have the power of reasoning (which (p-45) they may have for aught we know) they have the right to argue that the idea of the body has no objective foundation in fact, and though there is a mysterious sense of attraction and mutual influence running through them, these are nothing positively real ; the sole reality which is provable is in the isolation of these cells made by gaps that can never be crossed or bridged.

We know something about a system of explosive atoms whirling separately in a space which is immense compared to their own dimension. Yet we do not know why they should appear to us a solid piece of radiant mineral. And if there is an onlooker who at one glance can have the view of the immense time and space occupied by innumerable human individuals engaged in evolving a common history, the positive truth of their solidarity will be concretely evident to him and not the negative fact of their separateness.

The reality of a piece of iron is not provable if we take the evidence of the atom ; the only proof is that I see it as a bit of iron, and that it has certain reactions upon my consciousness. Any being from, say, Orion, who has the sight to see the atoms and not the iron, has the right to say that we human beings suffer from an agelong epidemic of hallucination. We need not quarrel with him but go on using the iron as it appears to us. Seers there have been who have said "Vedahametam", "I see", (p-46) and lived a life according to that vision. f And though our own sight may be blind we have ever bowed our head to them in reverence.

However, whatever name our logic may give to the truth of human unity, the fact can never be ignored that we have our greatest delight when we realize ourselves in others, and this is the definition of love. This love gives us the testimony of the great whole, which is the complete and final truth of man. It offers us the immense field where we can have our release from the sole monarchy of hunger, of the growling voice, snarling teeth and tearing claws, from the dominance of the limited material means, the source of cruel envy and ignoble deception, where the largest wealth of the human soul has been produced through sympathy and cooperation ; through disinterested pursuit of knowledge that recognizes no limit and is unafraid of all timehonoured tabus; through a strenuous cultivation of intelligence for service that knows no distinction of colour and clime. The Spirit of Love, dwelling in the boundless realm of the surplus, emancipates our consciousness from the illusory bond of the separateness of self; it is ever trying to spread its illumination in the human world. This is the spirit of civilization, which in all its best endeavour invokes our supreme Being for the only bond of unity that leads us to truth, namely, that of righteousness: (p-47)

Ya efco varno bahudha saktiyogat

. varnan anekan nihitartho dadhati

. vichaitti chante viavamadau

. sa devah sa no budhya subhaya samyunaktu.

"He who is one, above all colours, and who with his manifold power supplies the inherent needs of men of all colours, who is in the beginning and in the end of the world, is divine, and may he unite us in a relationship of good will."

Chapter III

THE SURPLUS IN MAN

THERE are certain verses from the Atharva Veda in which the poet discusses his idea of Man, indicating some transcendental meaning that can be translated as follows:

"Who was it that imparted form to man, gave him majesty, movement, manifestation and character, inspired him with wisdom, music and dancing? When his body was raised upwards he found also the oblique sides and all other directions in him he who is the Person, the citadel of the infinite being."

Tasmad vai vidvan purushamidan brahmeti manyate.

. "And therefore the wise man knoweth this person as Brahma."

. Sanatanam enam ahur utadya syat punarnavah.

. "Ancient they call him, and yet he is renewed even now today."

In the very beginning of his career Man asserted in his bodily structure his first proclamation of freedom against the established rule of Nature. At a certain bend in the path of evolution he refused to remain a fourfooted creature, and the position which he made his body to assume carried with it a permanent gesture of insubordination. For there could be no question that it was Nature's (p-49) own plan to provide all landwalking mammals with two pairs of legs, evenly distributed along their lengthy trunk heavily weighted with a head at the end. This was the amicable compromise made with the earth when threatened by its conservative downward force, which extorts taxes for all movements. The fact that man gave up such an obviously sensible arrangement proves his inborn mania for repeated reforms of constitution, for pelting amendments at every resolution proposed by Providence.

If we found a fourlegged table stalking about upright upon two of its stumps, the remaining two foolishly dangling by its sides, we should be afraid that it was either a nightmare or some supernormal caprice of that piece of furniture, indulging in a practical joke upon the carpenter's idea of fitness. The like absurd behaviour of Man's anatomy encourages us to guess that he was born under the influence of some comet of contradiction that forces its eccentric path against orbits regulated by Nature. And it is significant that Man should persist in his foolhardiness, in spite of the penalty he pays for opposing the orthodox rule of animal locomotion. He reduces by half the help of an easy balance of his muscles. He is ready to pass his infancy tottering through perilous experiments in making progress upon insufficient support, and followed all through his life by liability to sudden (p-50) downfalls resulting in tragic or ludicrous consequences from which lawabiding quadrupeds are free. This was his great venture, the relinquishment of a secure position of his limbs, which he could comfortably have retained in return for humbly salaaming the allpowerful dust at every step.

This capacity to stand erect has given our body its freedom of posture, making it easy for us to turn on all sides and realize ourselves at the centre of things. Physically, it symbolizes the fact that while animals have for their progress the prolongation of a narrow line Man has the enlargement of a circle. As a centre he finds his meaning in a wide perspective, and realizes himself in the magnitude of his circumference.

As one freedom leads to another, Man's eyesight also found a wider scope. I do not mean any enhancement of its physical power, which in many predatory animals has a better power of adjustment to light But from the higher vantage of our physical watchtower we have gained our view, which is not merely information about the location of things but their interrelation and their unity*

But the best means of the expression of his physical freedom gained by Man in his vertical position is through the emancipation of his hands. In our bodily organization these have attained the highest dignity for their skill) their grace, their useful activities, as well as for those that are above all uses. They are the most detached of all our limbs. Once they had their menial vocation as our carriers, but raised from their position as shudras, they at once attained responsible status as our helpers. When instead of keeping them underneath us we offered them their place at our side, they revealed capacities that helped us to cross the boundaries of animal nature.

This freedom of view and freedom of action have been accompanied by an analogous mental freedom in Man through his imagination, which is the most distinctly human of all our faculties. It is there to help a creature who has been left unfinished by his designer, undraped, undecorated, unarmoured and without weapons, and, what is worse, ridden by a Mind whose energies for the most part are not tamed and tempered into some difficult ideal of completeness upon a background which is bare. Like all artists he has the freedom to make mistakes, to launch into desperate adventures contradicting and torturing his psychology or physiological normality. This freedom is a divine gift lent to the mortals who are untutored and undisciplined ; and therefore the path of their creative progress is strewn with debris of devastation, and stages of their perfection haunted by apparitions of startling deformities. But, all the same, the very training of creation ever makes clear an aim which cannot be in any isolated freak of an individual mind or in that which is only limited to the strictly necessary.

Just as our eyesight enables us to include the individual fact of ourselves in the surrounding view, our imagination makes us intensely conscious of a life we must live which transcends the individual life and contradicts the biological meaning of the instinct of selfpreservation. It works at the surplus, and extending beyond the reservation plots of our daily life builds there the guest chambers of priceless value to offer hospitality to the worldspirit of Man. We have such an honoured right to be the host when our spirit is a free spirit not chained to the animal self. For free spirit is godly and alone can claim kinship with God.

Every true freedom that we may attain in any direction broadens our path of selfrealization, which is in superseding the self. The unimaginative repetition of life within a safe restriction imposed by Nature may be good for the animal, but never for Man, who has the responsibility to outlive his life in order to live in truth.

And freedom in its process of creation gives rise to perpetual suggestions of something further than its obvious purpose. For freedom is for expressing the infinite; it imposes limits in its works, not to keep them in permanence but to break them over and over again, and to reveal the endless in unending surprises. This implies a history of constant regeneration, a series of fresh beginnings and continual challenges to the old in order to reach a more and more perfect harmony with some fundamental ideal of truth.

Our civilization, in the constant struggle for a great Further, runs through abrupt chapters of spasmodic divergences. It nearly always begins its new ventures with a cataclysm ; for its changes are not mere seasonal changes of ideas gliding through varied periods of flowers and fruit They are surprises lying in ambuscade provoking revolutionary adjustments. They are changes in the dynasty of living ideals the ideals that are active in consolidating their dominion with strongholds of physical and mental habits, of symbols, ceremonials and adornments* But however violent may be the revolutions happening in whatever time or country, they never completely detach themselves from a common centre. They find their places in a history which is one.

The civilizations evolved in India or China, Persia or Judaea, Greece or Rome, are like several mountain peaks having different altitude, temperature, flora and fauna, and yet belonging to the same chain of hills. There are no absolute barriers of communication between them; their foundation is the same and they affect the meteorology of an atmosphere which is common to us all. This is at (p-54) the root of the meaning of the great teacher who said he would not seek his own salvation if all men were not saved ; for we all belong to a divine unity, from which our greatsouled men have their direct inspiration; they feel it immediately in their own personality, and they proclaim in their life, "I am one with the Supreme, with the Deathless, with the Perfect".

Man, in his mission to create himself, tries to develop in his mind an image of his truth according to an idea which he believes to be universal, and is sure that any expression given to it will persist through all time. This is a mentality absolutely superfluous for biological existence. It represents his struggle for a life which is not limited to his body. For our physical life has its thread of unity in the memory of the past, whereas this ideal life dwells in the prospective memory of the future* In the records of past civilizations, unearthed from the closed records of dust, we find pathetic efforts to make their memories uninterrupted through the ages, like the effort of a child who sets adrift on a paper boat his dream of reaching the distant unknown. But why is this desire? Only because we feel instinctively that in our ideal life we must touch all men and all times through the manifestation of a truth which is eternal and universal. And in order to give expression to it materials are gathered that are excellent and a (p-55) manner of execution that has a permanent value. For we mortals must offer homage to the Man of the everlasting life. In order to do so, we are expected to pay a great deal more than we need for mere living, and in the attempt we often exhaust our very means of livelihood, and even life itself.

The ideal picture which a savage imagines of himself requires glaring paints and gorgeous fineries, a rowdiness in ornaments and even grotesque deformities of overwrought extravagance* He tries to sublimate his individual self into a manifestation which he believes to have the majesty of the ideal Man. He is not satisfied with what he is in his natural limitations ; he irresistibly feels something beyond the evident fact of himself which only could give him worth. It is the principle of power, which, according to his present mental stage, is the meaning of the universal reality whereto he belongs, and it is his pious duty to give expression to it even at the cost of his happiness. In fact, through it he becomes one with his God, for him his God is nothing greater than power. The savage takes immense trouble, and often suffers tortures, in order to offer in himself a representation of power in conspicuous colours and distorted shapes, in acts of relentless cruelty and intemperate bravado of selfindulgence. Such an appearance of rude grandiosity evokes a loyal reverence in the members of his community and a (p-56) fear which gives them an aesthetic satisfaction because it illuminates for them the picture of a character which, as far as they know, belongs to ideal humanity. They wish to see in him not an individual, but the Man in whom they all are rep* resented. Therefore, in spite of their sufferings, they enjoy being overwhelmed by his exaggerations and dominated by a will fearfully evident owing to its magnificent caprice in inflicting injuries. They symbolize their idea of unlimited wilfulness in their gods by ascribing to them physical and moral enormities in their anatomical idiosyncracy and virulent vindictiveness crying for the blood of victims, in personal preferences indiscriminate in the choice of recipients and methods of rewards and punishments. In fact, these gods could never be blamed for the least wavering in their conduct owing to any scrupulousness accompanied by the emotion of pity so often derided as sentimentalism by virile intellects of the present day.

However crude all this may be, it proves that Man has a feeling that he is truly represented in something which exceeds himself. He is aware that he is not imperfect, but incomplete. He knows that in himself some meaning has yet to be realized. We do not feel the wonder of it, because it seems so natural to us that barbarism in Man is not absolute, that its limits are like the limits of the horizon. The call is deep in his mind the (p-57) call of his own inner truth, which is beyond his direct knowledge and analytical logic. And individuals are born who have no doubt of the truth of this transcendental Man. As our consciousness more and more comprehends it, new valuations are developed in us, new depths and delicacies of delight, a sober dignity of expression through elimination of tawdriness, of frenzied emotions, of all violence in shape, colour, words, or behaviour, of the dark mentality of Ku-Klux-Klanism.

Each age reveals its personality as dreamer in its great expressions that carry it across surging centuries to the continental plateau of permanent human history. These expressions may not be consciously religious, but indirectly they belong to Man's religion. For they are the outcome of the consciousness of the greater Man in the individual men of the race. This consciousness finds its manifestation in science, philosophy and the arts, in social ethics, in all things that carry their ultimate value in themselves. These are truly spiritual and they should all be consciously coordinated in one great religion of Man, representing his ceaseless endeavour to reach the perfect in great thoughts and deeds and dreams, in immortal symbols of art, revealing his aspiration for rising in dignity of being.

I had the occasion to visit the ruins of ancient Rome, the relics of human yearning towards the (p-58) immense, the sight of which teases our mind out of thought. Does it not prove that in the vision of a great Roman Empire the creative imagination of the people rejoiced in the revelation of its transcendental humanity? It was the idea of an Empire which was not merely for opening an outlet to the pentup pressure of overpopulation, or widening its field of commercial profit, but which existed as a concrete representation of the majesty of Roman personality, the soul of the people dreaming of a worldwide creation of its own for a fit habitation of the Ideal Man. It was Rome's titanic endeavour to answer the eternal question as to what Man truly was, as Man. And any answer given in earnest falls within the realm of religion, whatever may be its character ; and this answer, in its truth, belongs not only to any particular people but to us all. It may be that Rome did not give the most perfect answer possible when she fought for her place as a worldbuilder of human history, but she revealed the marvellous vigour of the indomitable human spirit which could say, "Bhumaiva sukhamf "Greatness is happiness itself". Her Empire has been sundered and shattered, but her faith in the sublimity of man still persists in one of the vast strata of human geology. And this faith was the true spirit of her religion, which had been dim in the tradition of her formal theology, merely supplying her with an emotional pastime and not with spiritual inspiration. In fact this theology fell far below her personality, and for that reason it went against her religion, whose mission was to reveal her humanity on the background of the eternal. Let us seek the religion of this and other people not in their gods but in Man, who dreamed of his own infinity and majestically worked for all time, defying danger and death.

Since the dim nebula of consciousness in Life's world became intensified into a centre of self in Man, his history began to unfold its rapid chapters ; for it is the history of his strenuous answers in various forms to the question rising from this conscious self of his, "What am I?" Man is not happy or contented as the animals are ; for his happiness and his peace depend upon the truth of his answer. The animal attains his success in a physical sufficiency that satisfies his nature. When a crocodile finds no obstruction in behaving like an orthodox crocodile he grins and grows and has no cause to complain. It is truism to say that Man also must behave like a man in order to find his truth. But he is sorely puzzled and asks in bewilderment: "What is it to be like a man? What am I?" It is not left to the tiger to discover what is his own nature as a tiger, nor, for the matter of that, to choose a special colour for his coat according to his taste.

But Man has taken centuries to discuss the ques- (p-60) tion of his own true nature and has not yet come to a conclusion. He has been building up elaborate religions to convince himself, against his natural inclinations, of the paradox that he is not what he is but something greater. What is significant about these efforts is the fact that in order to know himself truly Man in his religion cultivates the vision of a Being who exceeds him in truth and with whom also he has his kinship. These religions differ in details and often in their moral significance, but they have a common tendency. In them men seek their own supreme value, which they call divine, in some personality anthropomorphic in character. The Mind, which is abnormally scientific, scoffs at this ; but it should know that religion is not essentially cosmic or even abstract; it finds itself when it touches the Brahma in man; otherwise it has no justification to exist.

It must be admitted that such a human element introduces into our religion a mentality that often has its danger in aberrations that are intellectually blind, morally reprehensible and aesthetically repellent But these are wrong answers; they distort the truth of man and, like all mistakes in sociology, in economics or politics, they have to be fought against and overcome. Their truth has to be judged by the standard of human perfection and not by some arbitrary injunction that refuses to be confirmed by the tribunal of the human con-science. And great religions are the outcome of great revolutions in this direction causing fundamental changes of our attitude. These religions invariably made their appearance as a protest against the earlier creeds which had been unhuman, where ritualistic observances had become more important and outer compulsions more imperious. These creeds were, as I have said before, cults of power; they had their value for us, not helping us to become perfect through truth, but to grow formidable through possessions and magic control of the deity.

But possibly I am doing injustice to our ancestors. It is more likely that they worshipped power not merely because of its utility, but because they, in their way, recognized it as truth with which their own power had its communication and in which it found its fulfilment They must have naturally felt that this power was the power of will behind nature, and not some impersonal insanity that unaccountably always stumbled upon correct results. For it would have been the greatest depth of imbecility on their part had they brought their homage to an abstraction, mindless, heartless and purposeless; in fact, infinitely below them in its manifestation.

Chapter IV

SPIRITUAL UNION

WHEN Man's preoccupation with the means of livelihood became less insistent he had the leisure to come to the mystery of his own self, and could not help feeling that the truth of his personality had both its relationship and its perfection in an endless world of humanity. His religion, which in the beginning had its cosmic background of power, came to a higher stage when it found its background in the human truth of personality. It must not be thought that in this channel it was narrowing the range of our consciousness of the infinite. The negative idea of the infinite is merely an indefinite enlargement of the limits of things; in fact, a perpetual postponement of infinitude. I am told that mathematics has come to the conclusion that our world belongs to a space which is limited. It does not make us feel disconsolate. We do not miss very much and need not have a low opinion of space even if a straight line cannot remain straight and has an eternal tendency to come back to the point from which it started. In the Hindu Scripture the universe is described as an egg; that (p-63) is to say, for the human mind it has its circular shell of limitation. The Hindu Scripture goes still further and says that time also is not continuous and our world repeatedly comes to an end to begin its cycle once again. In other words, in the region of time and space infinity consists of everrevolving finitude.

But the positive aspect of the infinite is in advaitam, in an absolute unity, in which comprehension of the multitude is not as in an outer receptacle but as in an inner perfection that permeates and exceeds its contents, like the beauty in a lotus which is ineffably more than all the constituents of the flower. It is not the magnitude of extension but an intense quality of harmony which evokes in us the positive sense of the infinite in our joy, in our love. For advaitam is anandam; the infinite One is infinite Love. For those among whom the spiritual sense is dull, the desire for realization is reduced to physical possession, an actual grasping in space. This longing for magnitude becomes not an aspiration towards the great, but a mania for the big. But true spiritual realization is not through augmentation of possession in dimension or number. The truth that is infinite dwells in the ideal of unity which we find in the deeper relatedness. This truth of realization is not in space, it can only be realized in one's own inner spirit (p-64)

Ekadhaivanudrashtavyam etat aprameyam dhruvam.

. (This infinite and eternal has to be known as One.)

Para akasat aja atma "this birthless spirit is beyond space". For it is Purushahj it is the "Person".

The special mental attitude which India has in her religion is made clear by the word Yoga, whose meaning is to effect union. Union has its significance not in the realm of to have, but in that of to be. To gain truth is to admit its separateness, but to be true is to become one with truth. Some religions, which deal with our relationship with God, assure us of reward if that relationship be kept true. This reward has an objective value. It gives us some reason outside ourselves for pursuing the prescribed path. We have such religions also in India. But those that have attained a greater height aspire for their fulfilment in union with Narayana, the supreme Reality of Man, which is divine.

Our union with this spirit is not to be attained through the mind. For our mind belongs to the department of economy in the human organism. It carefully husbands our consciousness for its own range of reason, within which to permit our relationship with the phenomenal world* But it is the object of Yoga to help us to transcend the limits built up by Mind. On the occasions when these are overcome, our inner self is filled with joy, (p-65) which indicates that through such freedom we come into touch with the Reality that is an end in itself and therefore is bliss.

Once man had his vision of the infinite in the universal Light, and he offered his worship to the sun. He also offered his service to the fire with oblations. Then he felt the infinite in Life, which is Time in its creative aspect, and he said, "Yat kincha yadidam sarvam prana ejati nihsritam", "all that there is comes out of life and vibrates in it". He was sure of it, being conscious of Life's mystery immediately in himself as the principle of purpose, as the organized will, the source of all his activities. His interpretation of the ultimate character of truth relied upon the suggestion that Life had brought to him, and not the nonliving which is dumb. And then he came deeper into his being and said "Raso vai sah" 9 "the infinite is love itself ", the eternal spirit of joy. His religion, which is in his realization of the infinite, began its journey from the impersonal dyaus, "the sky", wherein light had its manifestation; then came to Life, which represented the force of selfcreation in time, and ended in purushak, the "Person", in whom dwells timeless love. It said, "Tarn vedyam purusham vedah", "Know him the Person who is to be realized", "Yatha ma vo mrityug parivya~ thah" "So that death may not cause you sorrow". For this Person is deathless in whom the individual (p-66) person has his immortal truth. Of him it is said :