The Importance of Armenian for Understanding the Development of the Proto- Indo-European Phonological System in Old Indic, Greek, and Italic

Allan R. Bomhard

Florence, SC

The paper explores the important role that Armenian has to play in understanding the development of the glottalic model of the Proto- Indo-European consonant system in Old Indic, Greek, and Italic.

INTRODUCTION

This is the last in a series of articles designed to demonstrate how the glottalic model of Proto-Indo-European consonantism is a viable alternative to the traditional reconstruction and can readily account for all of the early phonological developments in the older Indo-European daughter languages. The first paper, which was published in 2016, was entitled “The Glottalic Model of Proto- Indo-European Consonantism: Re-igniting the Dialog”. This paper dealt mainly with a review and refutation of all of the criticisms that have been leveled against the Glottalic Theory to date. The second paper, which was published in 2019 in the Journal of Indo- European Studies, is entitled “The Origins of Proto-Indo- European: The Caucasian Substrate Hypothesis”. This paper provides corroborating evidence for the Glottalic Theory on the basis of early language contact between Proto-Indo-European and primordial Northwest Caucasian languages. The third paper, which was published in Wékwos in 2019, is entitled “The Importance of Hittite and the Other Anatolian Daughter Languages for the Reconstruction of the Proto-Indo-European Phonological System”. This paper explores how Hittite and the other Anatolian daughter languages provide powerful support for the Glottalic Theory.

The current paper addresses the development of the revised Proto-Indo-European phonological system in the various non- Anatolian Indo-European daughter languages, concentrating, in particular, on Armenian, Old Indic (Indo-Aryan), Greek, and Italic. Here, Armenian has a crucial role to play in understanding the developments in the early prehistory of these daughter languages.

We will begin by looking at Disintegrating Indo-European and then discuss Germanic, Celtic, Slavic, and Baltic, after which we will move on to Armenian and finish with Indo-Iranian, Greek, and Italic. For the sake of simplicity and continuity, I will repeat (and expand upon) what I have previously written. Albanian and Tocharian will not be considered here (but see Bomhard 2018, vol. 1, Chapter 5).

DISINTEGRATING INDO-EUROPEAN

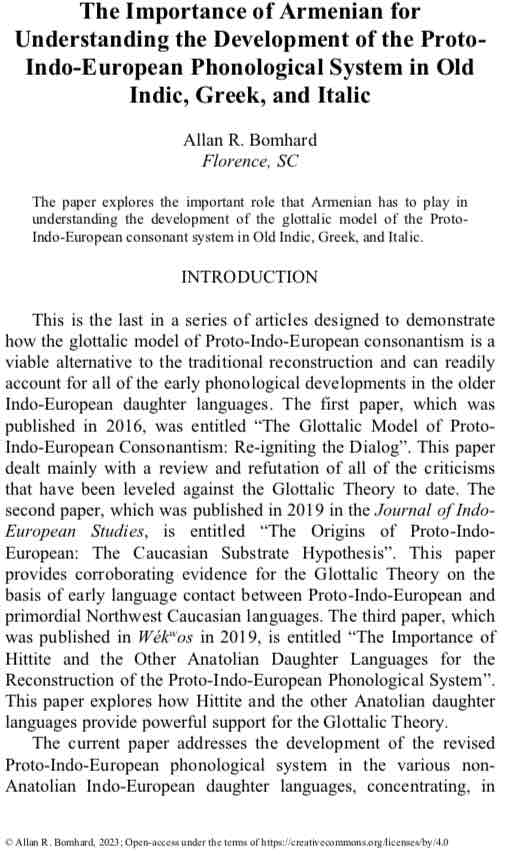

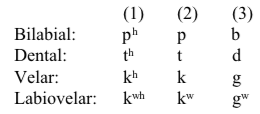

In my 2019 paper “The Importance of Hittite and the Other Anatolian Daughter Languages for the Reconstruction of the Proto- Indo-European Phonological System”, I expressed support for the theory that the Anatolian languages were the first to separate from the rest of the Indo-European speech community, and I proposed that the phonological system to be reconstructed for pre-Anatolian Proto-Indo-European was as shown below (column 1 is voiceless aspirated, column 2 is glottalized, and column 3 is plain voiced):

Furthermore, I noted that the following series of phonological changes may be assumed to have taken place in the Indo-European parent language after the separation of the Anatolian branch and before the emergence of the individual non-Anatolian Indo-European daughter languages:

- The laryngeals *H1 and *H4 were lost initially before vowels, while *H2 > *h and *H3 > *ɦ > *h in the same environment.

- Next, all medial and final laryngeals merged into *h.

The single remaining laryngeal *h was then lost initially before vowels (except in pre-Armenian) and medially between an immediately preceding vowel and a following non-syllabic. This latter change caused the compensatory lengthening of preceding short vowels, thus:

eHC > ēC

oHC > ōC

aHC > āC

iHC > īC

uHC > ūC- *h was preserved in all other positions. *h had a syllabic allophone, *h̥ , when between two non-syllabics. This syllabic allophone is the traditional schwa primum (*ə).

- Glottalization was probably lost in late Disintegrating Indo- European itself just as the individual non-Anatolian daughter languages were beginning to emerge.

- The earlier plain voiced stops developed into voiced aspirates (column 3 above), at least in some dialects of Disintegrating Indo-European.

- The *e ~ *a qualitative Ablaut of pre-Anatolian Proto-Indo- European developed into an *e ~ *o Ablaut.

- New Ablaut relationships developed as a result of the loss of laryngeals.

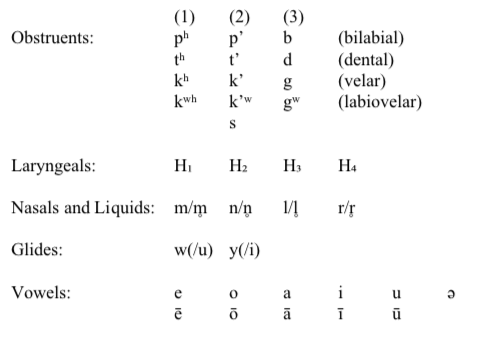

For the latest period of development of the Indo-European parent language, the stage I call “Disintegrating Indo-European” — after the separation of the Anatolian branch from the rest of the Indo-European speech community and before the emergence of the individual non-Anatolian Indo-European daughter languages —, I suggested that the Proto-Indo-European antecedent of the satəm daughter languages is to be reconstructed as follows (column 1 is voiceless aspirated, column 2 is glottalized [ejectives], and column 3 is voiced aspirated):

The most significant difference between the phonological system of the Disintegrating Indo-European antecedent of the satəm dialects and that of the centum dialects was in the treatment of the gutturals. In the centum dialects, the labiovelars did not become delabialized, and the palatovelars remained subphonemic.

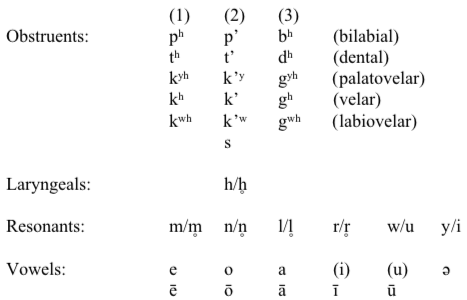

The phonological system of the Disintegrating Indo-European antecedent of the centum daughter languages, on the other hand, may be reconstructed thus (column 1 is voiceless aspirated, column 2 is glottalized, and column 3 is voiced aspirated:

Note:

Even though I have reconstructed a series of voiced aspirates above (column 3), such sounds are really only needed to explain developments in Armenian, Old Indic, Greek, and Italic, as we shall see below.

GERMANIC

To begin, I would like to address a statement made by Fulk in his recent book A Comparative Grammar of the Early Germanic Languages (Fulk 2018:100):

The chief implication of the glottalic theory for Germanic linguistics is that it permits Germanic (along with Armenian) to be regarded not as a highly innovative branch in its consonantism but as an exceptionally conservative one, whereas the IE languages usually regarded as hewing closest to the PIE consonant system, especially Sanskrit and Greek, turn out to do nothing of the sort. That Germanic should have remained so conservative while the European languages in closest proximity to it in prehistoric times all altered the inherited obstruents in similar ways is difficult to credit. And yet although the glottalic theory is not now widely supported, there is a considerable degree of concurrence that the reconstruction of PIE obstruents represented in §6.1 is implausible and awaits replacement by a creditable reconstruction. Nonetheless, it need not be the case that such an alternative reconstruction is what must be assumed for the latest stages of PIE, since it is of course possible that the typological peculiarities of PIE mentioned above are the consequence of an earlier obstruent system that had already changed before any of the extant IE families had developed individuating characteristics. That is to say, it is not a given that any IE language should directly reflect that earlier state of affairs rather than a later-developed obstruent system similar to that arrived at (in §6.1) by the comparative method. The supposition that Germanic is an especially archaic branch of IE is at all events unsupported by its verb system, which appears to be a simplification of that reconstructed for late PIE (§12.9), showing no marked resemblance to the Hittite verb system.

I do not understand the logic here. I see no problem whatsoever in viewing a particular language or branch as conservative in one area and innovative in another. This means that the innovations in the Germanic verb system do not preclude the retention of archaic features in the Germanic phonological system. (Note: This does not imply that there is any fault with Fulk’s book as a whole — it is an excellent monograph and a valuable resource, comprehensive in scope and current in its coverage of the field.) This same point is made by Hejná—Walkden (2022:262) in their discussion of the difference in the rates of change of noun morphology as opposed to verb morphology between Old English and Middle English:

If you pause at this point to compare the verbal endings in Old English with the ones presented for Middle English in the last chapter (§5.3.2), you’ll see that on the whole there’s not a huge amount of difference: the big changes in verbal morphology in English take place between the Middle and Modern periods. This is different for nominal morphology, which (as you’ll soon see) is considerably more complex in Old English than in Middle English. This kind of fluctuation in rates of change is not unusual! It’s not the case that all aspects of a language have to change at the same speed or at the same time, ...

Germanic, like Armenian, is extremely conservative in its phonology — the Disintegrating Indo-European consonant system is preserved better in these two branches than in any of the other daughter languages. Unlike Armenian, however, Germanic preserves the older contrast between velars and labiovelars, though, in the course of development, they first became voiceless fricatives and then, at a later date and under certain specific conditions, voiced fricatives (see below for details). Armenian, on the other hand, belongs to the satəm group of languages and is, therefore, descended from that form of Disintegrating Indo- European in which this contrast was replaced by a contrast between palatovelars and plain velars.

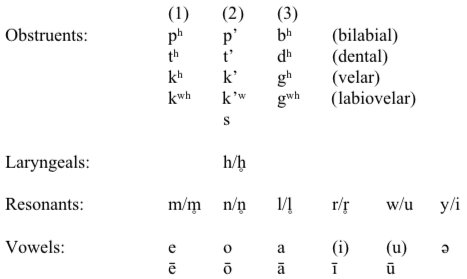

In the pre-Germanic dialect of Disintegrating Indo-European, the glottalics were deglottalized, resulting in the following system, with the three-way contrast (1) voiceless aspirated ~ (2) plain (unaspirated) voiceless ~ (3) plain voiced (note: voiced aspirates are not needed in order to account for the Germanic develop- ments):

Note: Glottalization may have been preserved in pre-Germanic in series 2 above. Glottalization has been proposed to account for the

The following series of changes can be postulated for the development of the Disintegrating Indo-European system of obstruents into the system found in Proto-Germanic:

- The voiceless aspirates (series 1) become voiceless fricatives: *ph, *th, *kh, *kwh > *f, *þ, *χ, *χw, except after *s-.

- Later, the resulting voiceless fricatives became the voiced fricatives *ƀ, *ð, *ᵹ, and *ᵹw, respectively, except (A) initially and (B) medially between vowels when the accent fell on the contiguous preceding syllable (Verner’s Law). *s was also changed to *z under the same conditions. Cf. Fulk 2018:107— 110.

*b remained initially, in gemination, and after nasals; *d initially, in gemination, and after nasals, *l, *z, and *g; and *g only in gemination and after nasals. In other positions, however, *b, *d, *g were changed into the voiced fricatives *ƀ, *ð, *ᵹ, respectively. *gw became *ᵹ initially and *w medially (cf. Wright—Wright 1925:131).

The resulting Proto-Germanic consonant system may thus be reconstructed as follows (cf. Fulk 2018:102—112; Moulton 1972):